TSHR Variant Screening and Phenotype Analysis in 367 Chinese Patients With Congenital Hypothyroidism

- Lisa Victoria Larsen

- Oct 10, 2024

- 19 min read

Written by Hai-Yang Zhang, M.D.,#1,* Feng-Yao Wu, M.D.,#1,* Xue-Song Li, M.D.,2 Ping-Hui Tu, M.D.,1 Cao-Xu Zhang, M.D.,1 Rui-Meng Yang, M.D., Ph.D.,1 Ren-Jie Cui, Ph.D.,1 Chen-Yang Wu, M.D.,1 Ya Fang, M.D., Ph.D.,1 Liu Yang, M.S.,1 Huai-Dong Song, M.D., Ph.D.,1 and Shuang-Xia Zhao, M.D., Ph.D.1

Ann Lab Med. 2024 Jul 1; 44(4): 343–353.

Published online 2024 Mar 4. doi: 10.3343/alm.2023.0337

Abstract

Background

Genetic defects in the human thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor (TSHR) gene can cause congenital hypothyroidism (CH). However, the biological functions and comprehensive genotype–phenotype relationships for most TSHR variants associated with CH remain unexplored. We aimed to identify TSHR variants in Chinese patients with CH, analyze the functions of the variants, and explore the relationships between TSHR genotypes and clinical phenotypes.

Methods

In total, 367 patients with CH were recruited for TSHR variant screening using whole-exome sequencing. The effects of the variants were evaluated by in-silico programs such as SIFT and polyphen2. Furthermore, these variants were transfected into 293T cells to detect their Gs/cyclic AMP and Gq/11 signaling activity.

Results

Among the 367 patients with CH, 17 TSHR variants, including three novel variants, were identified in 45 patients, and 18 patients carried biallelic TSHR variants. In vitro experiments showed that 10 variants were associated with Gs/cyclic AMP and Gq/11 signaling pathway impairment to varying degrees. Patients with TSHR biallelic variants had lower serum TSH levels and higher free triiodothyronine and thyroxine levels at diagnosis than those with DUOX2 biallelic variants.

Conclusions

We found a high frequency of TSHR variants in Chinese patients with CH (12.3%), and 4.9% of cases were caused by TSHR biallelic variants. Ten variants were identified as loss-of-function variants. The data suggest that the clinical phenotype of CH patients caused by TSHR biallelic variants is relatively mild. Our study expands the TSHR variant spectrum and provides further evidence for the elucidation of the genetic etiology of CH.

Keywords: Congenital hypothyroidism, Recessive inheritance, Thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor, Variant, Whole-exome sequencing

Introduction

Congenital hypothyroidism (CH) is a disease characterized by impairments in neurodevelopment and physical growth and development owing to dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis present at birth [1]. CH is the most common congenital endocrine metabolic disease, with a global prevalence of 1/2,000–1/3,000 [1]. With the recent developments in gene sequencing technologies, an increasing number of pathogenic genes related to CH, including genes related to thyroid dysgenesis and dyshormonogenesis, have been reported. Among these, the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor (TSHR) gene is one of the widely investigated candidate genes [2, 3].

The human TSHR gene is located on chromosome 14q31 and encodes a G-protein-coupled receptor that consists of a seven-transmembrane domain (TMD) and a large extracellular domain (ECD) responsible for high-affinity hormone binding. The TSHR is activated upon binding to TSH and induces two signal transduction pathways: the Gs/cyclic AMP (cAMP) pathway and the Gq/11 phospholipase C pathway, which contribute to thyroglobulin iodination and cell proliferation, whereas the Gs pathway is also responsible for iodine uptake regulation in thyrocytes [4, 5]. Both pathways are important for thyroid hormone synthesis and thyroid development [4, 6].

Loss-of-function (LOF) variants in the TSHR can cause TSH resistance, which leads to congenital nongoitrous hypothyroidism 1 (OMIM: 275200), which presents a broad spectrum of phenotypes, ranging from severe congenital hypothyroidism to mild euthyroid hyperthyrotropinemia [2, 7-10]. These LOF variants may result in a thyroid gland of normal position and size or in thyroid dysgenesis [11]. LOF variants in TSHR were first described in patients with TSH resistance in 1995 [12]. Up to April 2021, 202 TSHR variants have been reported and documented in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD). However, the biological functions of most TSHR variants remain unknown, and genotype–phenotype relationships have not yet been clearly established.

We previously identified 15 TSHR variants in 13 out of 220 Chinese patients with CH [13]. In the present study, we enrolled an additional 367 patients with CH, expanding the sample for screening TSHR variants and characterizing the phenotypes of patients with CH carrying TSHR variants. The biological functions of the variants were investigated through a series of in vitro experiments. We expected this study to deepen our understanding of the genetic landscape and functional consequences of TSHR variants and to provide valuable insights into the clinical management of patients harboring TSHR variants.

Materials and methods

Patients

In total, 367 patients were enrolled from the Chinese Han populations in Jiangsu province, Fujian province, Anhui province, and Shanghai. Among them, 362 patients (98.7%) received neonatal CH screening, which was performed using filter-paper blood spots (obtained through a heel prick) within 3–5 days after birth. Patients with TSH levels ≥10 μIU/mL at initial screening were recalled for re-examination using an immune-chemiluminescence assay (UniCelDxI 800; Beckman, Indianapolis, IN, USA) to determine the levels of TSH, free triiodothyronine (FT3), and free thyroxine (FT4). The details of the diagnostic standards for CH have been described in our previous study [14]. In addition, five patients who were on l-thyroxine replacement therapy were recruited from outpatient clinics. Although these patients were not neonatally screened, they had a clear history of CH. Thyroid morphology was determined by experienced radiologists through thyroid ultrasound or technetium-99m scanning. Written informed consent to participate was provided by the participants’ legal guardians, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China (approval number: 2016-76-T33).

Whole-exome sequencing (WES)

WES was performed as previously described [15]. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood, fragmented to 200–300 bp, and ligated to adapters using the KAPA HyperPrep Kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Exonic hybrid capture was performed according to the instructions in the Roche SeqCap EZ Library SR User’s Guide. Library quality and levels were determined using the MAN CLS140145 DNA 1 K Chip (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) and the PE LabChip GXII Touch (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). The Illumina HiSeq 3000 system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was then used to sequence the paired-end libraries with 150-bp paired-end reads, averaging approximately 100× depth.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. Quantitative variables are presented as mean±SE. The normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test and intergroup comparisons were performed using Student’s unpaired t-test (for normally distributed data) or the Mann–Whitney U test (for non-normally distributed data), as appropriate. Categorical variables are presented as percentages and were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher exact test, as appropriate. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Additional methods are available in the Supplemental Materials.

Results

Clinical characteristics of 367 patients with CH

In total, 367 patients with CH, including 196 boys and 171 girls, were recruited in this study. The mean serum FT3, FT4, and TSH levels at diagnosis were 4.87 pmol/L, 10.55 pmol/L, and 77.57 μIU/mL, respectively (reference ranges: FT3, 3.85–6.01 pmol/L; FT4, 7.46–21.11 pmol/L; TSH, 0.34–5.60 μIU/mL). Based on the serum FT4 level at diagnosis, CH was classified as severe (FT4<5 pmol/L), moderate (5 pmol/L≤FT4<10 pmol/L), or mild (FT4≥10 pmol/L) [16]. In the present cohort, 49.1% of patients had moderate or severe CH, and 50.9% of patients presented with mild CH. There were no significant differences in hormone levels and other clinical characteristics between boys and girls (Table 1).

Screening for TSHR variants in Chinese patients with CH and pedigree analysis

Among the 367 patients with CH, 45 patients carried 17 non-synonymous TSHR variants, including 16 missense variants and one nonsense variant. The TSHR variant frequency was 12.3% (45/367). Out of 17 variants, three (p.S237G, p.W546C, and p.M728T) were first reported in this study, and 10 were recurrent variants (p.G132R, p.G245S, p.S305R, p.N432S, p.R450H, p.F525S, p.R609X, p.Y613C, p.V689G, and p.E758K). p.R450H, which is a hotspot variant in the Chinese population, had the highest frequency (2.7%) (Table 2).

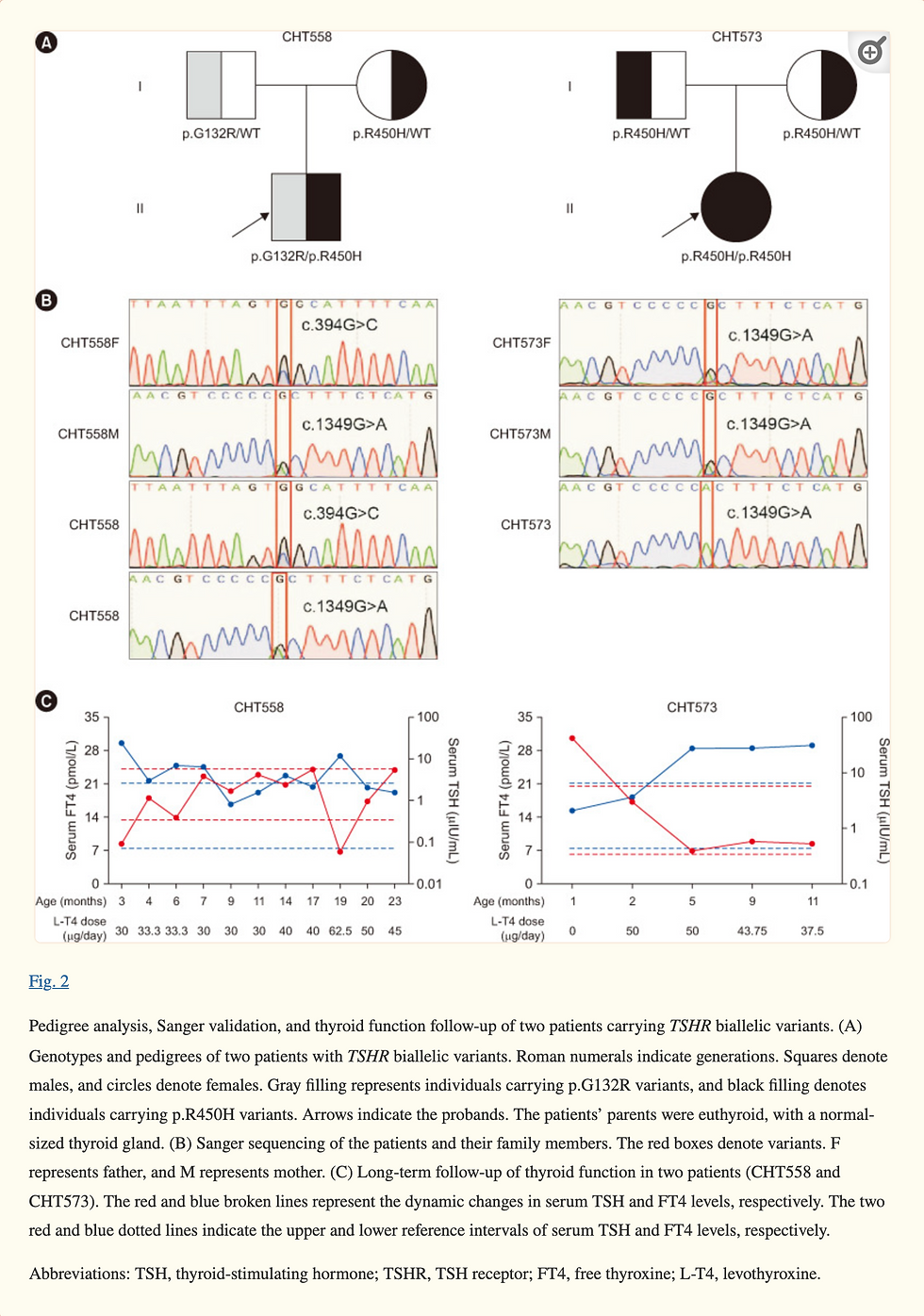

Four of the 17 variants were located in the leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain of the TSHR protein (Fig. 1A). Conservation analysis of the three novel variants showed that p.W546C was highly conserved across species, whereas p.M728T was less conserved (Fig. 1B). Out of the 45 patients with TSHR variants, 18 patients carried biallelic variants. We conducted a long-term follow-up of two patients with TSHR biallelic variants (CHT558 and CHT573) and collected blood samples from their parents for pedigree analysis. Sanger sequencing showed that the biallelic variants carried by the patients were inherited from their father and mother separately, which is in line with an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern (Fig. 2).

Pathogenicity prediction of detected TSHR variants

The potential effects of the 17 variants identified were assessed using in silico programs (SIFT, Polyphen-2, Mutation Taster, and M-CAP). All four programs predicted that the variants p.I216T, p.G245S, p.A275T, p.N432S, p.R450H, p.A526T, p.R531W, p.W546C, p.Y613C, and p.V689G were detrimental to TSHR protein function and that the novel p.M728T variant was harmless. The prediction results of the other variants were inconsistent among the four programs (Supplemental Data Table S1).

Subsequently, we predicted the three-dimensional structure of the wild-type (WT) and three novel mutant proteins using in silico tools. In the novel variant p.S237G, a polar neutral serine was replaced with a non-polar aliphatic glycine, disrupting the hydrogen bond between serine 237 and lysine 211 (Supplemental Data Fig. S1A). For the p.W546C variant, the aromatic tryptophan residue at 546 was mutated to a neutral cysteine, disrupting the hydrogen bond between tryptophan 546 and asparagine 455, destabilizing the helix (Supplemental Data Fig. S1B). As for p.M728T, the model confidence at amino acid 738 was very low; therefore, it was not analyzed.

The American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) issued new guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants in 2015, describing a process for classifying variants into five categories based on criteria related to typical variant evidence types (such as population data, computational data, functional data, and segregation data). Variants are classified as pathogenic (P), likely pathogenic (LP), variants of uncertain significance (VUS), likely benign (LB), or benign (B) [17]. Based on the available evidence, the pathogenicity of the 17 variants identified was classified according to the ACMG guidelines and standards. Five variants (p.G132R, p.N432S, p.R450H, p.F525S, and p.R609X) were classified as P or LP, and p.M728T was classified as LB. The remaining 11 variants were classified as VUS (Supplemental Data Table S1).

Clinical characteristics of CH patients with TSHR variants

The clinical phenotypes of the 45 CH patients with TSHR variants were compared with those of the 322 CH patients without TSHR variants. There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of hormone levels, age at diagnosis, and initial levothyroxine dose (Supplemental Data Table S2).

Thyroid functional information at diagnosis was collected for 25 out of 45 patients who harbored TSHR variants, including four patients with severe CH, seven with moderate CH, and 14 with mild CH. One patient (CHT241) harboring TSHR variants had thyroid dysgenesis (Supplemental Data Table S3). Among the seven patients with TSHR biallelic variants, only one patient showed moderate CH, and the remaining six patients presented with mild CH. However, patients with the TSHR monoallelic variant can present with mild to severe CH. Surprisingly, we found that the patients with the TSHR monoallelic variant had more severe hypothyroidism, with lower FT4 levels (9.58±1.50 vs. 15.87±1.18, P=0.020) at diagnosis, than patients with TSHR biallelic variants (Fig. 3A–3C).

Dual oxidase 2 (DUOX2) is a key protein for thyroid hormone synthesis, and DUOX2 is the most frequently mutated gene in Chinese patients with CH [14, 18]. We compared the clinical characteristics of patients with TSHR or DUOX2 biallelic variants in the present cohort. Compared with CH patients with DUOX2 biallelic variants, patients with TSHR biallelic variants had lower serum TSH levels and higher FT3 and FT4 levels at diagnosis (TSH: 52.96±17.84 vs. 105.77±5.48, P=0.012; FT3: 5.71±0.43 vs. 4.47±0.15, P=0.025; FT4: 15.87±1.18 vs. 7.20±0.45, P<0.001) (Fig. 3D–3F). In patients with DUOX2 variants, hypothyroidism may vary with age, whereas in patients with TSHR variants, it tends to remain stable over time. Therefore, we compared thyroid function at 6 months and 3 yrs of age between patients carrying TSHR biallelic variants and those carrying DUOX2 biallelic variants. Interestingly, patients harboring TSHR biallelic variants exhibited higher FT4 levels at both 6 months and 3 yrs of age than patients carrying DUOX2 biallelic variants (6 months: 20.60±1.27 vs. 16.77±0.65, P=0.041; 3 yrs: 22.72±1.73 vs. 16.83±0.96, P=0.019) (Supplemental Data Fig. S2).

Functional assessment of the TSHR variants in vitro

The eight variants (p.G132R, p.I216T, p.G245S, p.N432S, p.R450H, p.F525S, p.A526T, and p.V689G) detected in 18 patients with TSHR biallelic variants and the three novel variants (p.S237G, p.W546C, and p.M728T) were selected for molecular function assessment. The variants were transiently transfected into 293T cells, and Gs/cAMP and Gq/11 signal transduction were investigated by measuring cAMP levels and luciferase activity, respectively. Compared with 293T cells transfected with the WT plasmid, cAMP production in response to bovine TSH (bTSH) was significantly reduced in cells transfected with the p.G132R, p.I216T, p.S237G, p.G245S, p.N432S, p.R450H, p.F525S, p.A526T, and p.W546C mutant plasmids. However, the p.V689G and p.M728T variants did not affect cAMP production (Fig. 4A). The p.G132R, p.I216T, p.S237G, p.G245S, p.F525S, p.A526T, p.W546C, and p.V689G variants showed partial Gq/11 signaling activity (14%–57%), whereas activity was almost abrogated for the p.N432S and p.R450H variants (<10%) after stimulation with 100 U/L bTSH. The p.M728T variant had no effect on Gq/11 signaling (Fig. 4B).

We next investigated the protein expression and subcellular localization of the three novel variants (p.S237G, p.W546C, and p.M728T) in 293T cells. Western blot analysis showed no significant differences in protein expression between the WT and the three mutants (Supplemental Data Fig. S3A and 3B). Subcellular localization analysis showed that the WT and three mutant TSHR proteins all localized to the cell membrane in an intact manner (Supplemental Data Fig. S3C).

Discussion

Through comprehensive screening, we identified 17 distinct TSHR variants in 367 CH patients in China. We found a high frequency of TSHR variants in Chinese patients with CH (45/367, 12.3%), with 4.9% of patients carrying biallelic TSHR variants. We identified three novel variants (p.S237G, p.W546C, and p.M728T), two of which (p.S237G and p.W546C) impaired TSHR biological functions in the Gs/cAMP and Gq/11 pathways.

Seventeen non-synonymous TSHR variants were identified in 45 CH patients, with a detection rate of 12.3%, which is higher than the rates reported in most domestic studies [13, 19-21] but lower than those in two cohort studies in Italy and Korea [22, 23]. Most TSHR LOF variants reported to date are located in exons 1, 4, 6, and 10 [11]. In this study, 12 of the 17 identified variants were located in exon 10, whereas none were located in exons 1, 4, and 6. These findings suggest that there may be regional and ethnic differences in the spectrum of TSHR variants. In addition, we found a hotspot variant, p.R450H, which is one of the most common TSHR LOF variants and has been demonstrated to have a founder effect in Japan [24].

Notably, among the 45 patients carrying TSHR variants, 18 carried biallelic variants. The total residual Gs/cAMP and Gq/11 pathway signaling activities in CH patients with TSHR biallelic variants were calculated as the sum of pathway signaling activities from both TSHR variant alleles divided by two. Two patients (CHT385 and CHT573) harboring the p.R450H homozygous variant, who had 35% Gs/cAMP signaling pathway activity and 6% Gq/11 signaling pathway activity, had clinically similar phenotypes and presented with mild hypothyroidism. Patient CHT506, who carried the p.G132R homozygous variant, had a 62% reduction in Gs/cAMP signaling pathway activity and 70% Gq/11 signaling pathway activity and was diagnosed as having moderate CH, with serum TSH and T4 levels of 150.00 μIU/mL and 9.27 pmol/L, respectively. Patient CHT436, who harbored the p.N432S/p.R450H biallelic variants with residual Gs/cAMP and Gq/11 signaling pathway activities of 32% and 8%, respectively, presented with mild CH, with serum TSH and FT4 levels of 27.26 μIU/mL and 18.66 pmol/L. Patients CHT445 and CHT516 carried the p.G132R/p.R450H biallelic variants, with residual Gs/cAMP and Gq/11 signaling pathway activities of 37% and 18%, respectively. They both exhibited mild CH. Patient CHT553 harboring the p.R450H/p.F525S biallelic variants had 30% and 32% residual Gs/cAMP and Gq/11 signaling pathway activities, respectively, and was diagnosed as having mild CH, with serum TSH and FT4 levels of 25.56 μIU/mL and 15.96 pmol/L, respectively (Supplemental Data Table S4).

These functional experimental results in patients with TSHR biallelic variants support the hypothesis that TSHR variants can cause the onset of CH. Pedigree analysis of two patients showed that CH caused by TSHR variants is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, which is consistent with previous findings [12, 25, 26].

LOF TSHR variants result in variable TSH resistance manifested as euthyroid hyperthyrotropinemia with a normal thyroid gland (fully compensated TSH resistance), mild hypothyroidism with a normal thyroid gland (partially compensated TSH resistance), or severe hypothyroidism with thyroid dysgenesis (uncompensated TSH resistance) [2]. In the present study, out of seven patients with TSHR biallelic variants, six patients presented with mild hypothyroidism, and only one patient presented with moderate hypothyroidism. Moreover, patients with TSHR biallelic variants had milder hypothyroidism than those with DUOX2 biallelic variants. These findings indicate that the phenotypes of CH caused by TSHR defects are milder and associated with completely or partially compensated TSH resistance.

The TSHR is a G-protein-coupled receptor with a TMD domain and a large ECD, which comprises an LRR domain involved in hormone binding specificity and a hinge region, linking the LRR domain to the TMD [11, 27]. TSHR activation results in intracellular signaling via the Gs protein, which leads to cAMP cascade activation, and via the Gq protein, which leads to phospholipase C cascade activation. In the present study, four variants (p.G132R, p.I216T, p.S237G, and p.G245S) were located in the LRR domain, and they caused varying degrees of impairment to the Gs/cAMP and Gq/11 signaling pathways. The novel p.S237G variant had no effect on the expression and membrane localization of the TSHR protein but partially hindered Gs/cAMP and Gq/11 signaling. This may be attributed to the replacement of amino acids altering the TSHR protein structure, thereby decreasing its ability to bind to TSH. The novel p.W546C variant, located in the fourth TMD of TSHR, is highly conserved among species. In silico tools predicted that this missense variant is detrimental to protein stability and function. In vitro experiments demonstrated that the p.W546C variant damages receptor function by affecting the Gs/cAMP and Gq/11 signaling pathways.

p.M728T, another novel variant identified in the present study, is located in the C-terminal intracellular region of TSHR. Chazenbalk, et al. [28] confirmed that the removal of the C-terminal 2/3 residues (Q709–L764) of TSHR did not impair receptor function. Concurrently, functional experiments in the present study showed that the p.M728T variant did not interfere with the Gs/cAMP or Gq/11 pathway. Numerous studies have confirmed that the hotspot variant p.R450H not only results in reduced cAMP activity and severely impaired Gq/11 pathway activity but also reduces the TSH binding ability of TSHR [5, 13, 24, 29], which is consistent with our findings.

The phenotypes of the TSHR monoallelic variant are reportedly always mild, whereas biallelic variants are often associated with a more severe phenotype [7]. However, we found that patients with the TSHR monoallelic variant presented with mild to severe CH. Therefore, we compared thyroid function at diagnosis in patients with monoallelic and biallelic TSHR variants. Surprisingly, patients with the TSHR monoallelic variant had lower FT4 levels, which may be because of the following reasons. First, in our cohort, 12 of 27 patients with the TSHR monoallelic variant harbored biallelic variants in 21 other CH pathogenic genes (NKX2-1, NKX2-5, FOXE1, PAX8, HHEX, TPO, SLC5A5, TG, DUOX2, DUOXA2, TSHR, SLC26A4, IYD, DIO1, DIO2, THRA, THRB, DUOX1, DUOXA1, GNAS, and SLC16A2) as described in our previous study [14] (Supplemental Data Table S3).

Compared with patients with TSHR biallelic variants, patients with oligogenic variants, including in TSHR, had lower FT4 levels and higher TSH levels at diagnosis, whereas patients with only a TSHR monoallelic variant showed no difference in thyroid function at diagnosis (Supplemental Data Fig. S4), which partially explains why patients with the TSHR monoallelic variant presented more severe hypothyroidism than those with TSHR biallelic variants. Second, the genetic etiology of CH is largely unknown, and patients with the TSHR monoallelic variant may also carry novel CH-causative genes, leading to a more severe phenotype. Finally, environmental modifiers, such as iodine intake and ethnicity, should be considered in addition to genetic factors to explain this phenotypic variation. For example, Vigone, et al. [30] reported phenotypic differences between two brothers harboring the same genetic variants attributed to different neonatal iodine supplies, which suggested that the different neonatal iodine supplies acted as disease modifiers.

This study had some limitations. First, among the 18 patients carrying biallelic TSHR variants, pedigree analysis was conducted for only two families. Second, we did not clarify whether patients carrying TSHR variants require lifelong thyroxine therapy. Third, the pathogenic mechanism related to the presence of a heterozygous sequence variant in TSHR in patients with CH was not fully identified. In future work, we will mine and analyze unknown pathogenic genes in CH to gain insight into the molecular mechanisms of CH pathogenesis.

In conclusion, we reported 17 TSHR variants in 367 Chinese patients with CH and investigated the biological function of 11 variants (eight biallelic and three novel variants). Two novel variants (p.S237G and p.W546C) impair TSHR protein biological function by interfering with Gs/cAMP and Gq/11 signaling. Characterization of the phenotypes of patients with TSHR variants revealed that TSHR biallelic variants cause mild CH. The present study expanded the TSHR variant spectrum and provided further evidence for the elucidation of the genetic etiology of CH.

References

1. van Trotsenburg P, Stoupa A, Léger J, Rohrer T, Peters C, Fugazzola L, et al. Congenital hypothyroidism: a 2020-2021 consensus guidelines update-an ENDO-European Reference Network Initiative endorsed by the European Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and the European Society for Endocrinology. Thyroid. 2021;31:387–419. doi: 10.1089/thy.2020.0333. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. Kostopoulou E, Miliordos K, Spiliotis B. Genetics of primary congenital hypothyroidism-a review. Hormones (Athens) 2021;20:225–36. doi: 10.1007/s42000-020-00267-x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Stoupa A, Kariyawasam D, Muzza M, de Filippis T, Fugazzola L, Polak M, et al. New genetics in congenital hypothyroidism. Endocrine. 2021;71:696–705. doi: 10.1007/s12020-021-02646-9. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Winkler F, Kleinau G, Tarnow P, Rediger A, Grohmann L, Gaetjens I, et al. A new phenotype of nongoitrous and nonautoimmune hyperthyroidism caused by a heterozygous thyrotropin receptor mutation in transmembrane helix 6. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:3605–10. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0112. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Narumi S, Nagasaki K, Ishii T, Muroya K, Asakura Y, Adachi M, et al. Nonclassic TSH resistance: TSHR mutation carriers with discrepantly high thyroidal iodine uptake. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E1340–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0070. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Kero J, Ahmed K, Wettschureck N, Tunaru S, Wintermantel T, Greiner E, et al. Thyrocyte-specific Gq/G11 deficiency impairs thyroid function and prevents goiter development. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2399–407. doi: 10.1172/JCI30380. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Persani L, Calebiro D, Cordella D, Weber G, Gelmini G, Libri D, et al. Genetics and phenomics of hypothyroidism due to TSH resistance. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;322:72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.01.008. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Alberti L, Proverbio MC, Costagliola S, Romoli R, Boldrighini B, Vigone MC, et al. Germline mutations of TSH receptor gene as cause of nonautoimmune subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2549–55. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.6.8536. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Schoenmakers N, Chatterjee VK. Thyroid gland: TSHR mutations and subclinical congenital hypothyroidism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11:258–9. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.27. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Grasberger H, Refetoff S. Resistance to thyrotropin. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;31:183–94. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2017.03.004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Cassio A, Nicoletti A, Rizzello A, Zazzetta E, Bal M, Baldazzi L. Current loss-of-function mutations in the thyrotropin receptor gene: when to investigate, clinical effects, and treatment. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2013;5 Suppl 1:29–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Sunthornthepvarakul T, Gottschalk ME, Hayashi Y, Refetoff S. Brief report: resistance to thyrotropin caused by mutations in the thyrotropin-receptor gene. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:155–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501193320305. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Fang Y, Sun F, Zhang RJ, Zhang CR, Yan CY, Zhou Z, et al. Mutation screening of the TSHR gene in 220 Chinese patients with congenital hypothyroidism. Clin Chim Acta. 2019;497:147–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2019.07.031. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Sun F, Zhang JX, Yang CY, Gao GQ, Zhu WB, Han B, et al. The genetic characteristics of congenital hypothyroidism in China by comprehensive screening of 21 candidate genes. Eur J Endocrinol. 2018;178:623–33. doi: 10.1530/EJE-17-1017. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Yang RM, Zhan M, Zhou QY, Ye XP, Wu FY, Dong M, et al. Upregulation of GBP1 in thyroid primordium is required for developmental thyroid morphogenesis. Genet Med. 2021;23:1944–51. doi: 10.1038/s41436-021-01237-3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Léger J, Olivieri A, Donaldson M, Torresani T, Krude H, van Vliet G, et al. European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology consensus guidelines on screening, diagnosis, and management of congenital hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:363–84. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1891. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–24. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Sun F, Zhang RJ, Cheng F, Fang Y, Yang RM, Ye XP, et al. Correlation of DUOX2 residual enzymatic activity with phenotype in congenital hypothyroidism caused by biallelic DUOX2 defects. Clin Genet. 2021;100:713–21. doi: 10.1111/cge.14065. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Fu C, Wang J, Luo S, Yang Q, Li Q, Zheng H, et al. Next-generation sequencing analysis of TSHR in 384 Chinese subclinical congenital hypothyroidism (CH) and CH patients. Clin Chim Acta. 2016;462:127–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2016.09.007. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Wang H, Kong X, Pei Y, Cui X, Zhu Y, He Z, et al. Mutation spectrum analysis of 29 causative genes in 43 Chinese patients with congenital hypothyroidism. Mol Med Rep. 2020;22:297–309. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2020.11078. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Fan X, Fu C, Shen Y, Li C, Luo S, Li Q, et al. Next-generation sequencing analysis of twelve known causative genes in congenital hypothyroidism. Clin Chim Acta. 2017;468:76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2017.02.009. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22. Shin JH, Kim HY, Kim YM, Lee H, Bae MH, Park KH, et al. Genetic evaluation of congenital hypothyroidism with gland in situ using targeted exome sequencing. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2021;51:73–81. doi: 10.5005/jp/books/13094_9. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. Nicoletti A, Bal M, De Marco G, Baldazzi L, Agretti P, Menabò S, et al. Thyrotropin-stimulating hormone receptor gene analysis in pediatric patients with non-autoimmune subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4187–94. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0618. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

24. Narumi S, Muroya K, Abe Y, Yasui M, Asakura Y, Adachi M, et al. TSHR mutations as a cause of congenital hypothyroidism in Japan: a population-based genetic epidemiology study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1317–23. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1767. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Ma SG, Fang PH, Hong B, Yu WN. The R450H mutation and D727E polymorphism of the thyrotropin receptor gene in a Chinese child with congenital hypothyroidism. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2010;23:1339–44. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2010.209. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Park SM, Clifton-Bligh RJ, Betts P, Chatterjee VK. Congenital hypothyroidism and apparent athyreosis with compound heterozygosity or compensated hypothyroidism with probable hemizygosity for inactivating mutations of the TSH receptor. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2004;60:220–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.01967.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

27. Mueller S, Szkudlinski MW, Schaarschmidt J, Günther R, Paschke R, Jaeschke H. Identification of novel TSH interaction sites by systematic binding analysis of the TSHR hinge region. Endocrinology. 2011;152:3268–78. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-0153. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

28. Chazenbalk GD, Nagayama Y, Russo D, Wadsworth HL, Rapoport B. Functional analysis of the cytoplasmic domains of the human thyrotropin receptor by site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:20970–5. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)45312-9. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Sugisawa C, Abe K, Sunaga Y, Taniyama M, Hasegawa T, Narumi S. Identification of compound heterozygous TSHR mutations (R109Q and R450H) in a patient with nonclassic TSH resistance and functional characterization of the mutant receptors. Clin Pediatr Endocrinol. 2018;27:123–30. doi: 10.1297/cpe.27.123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

30. Vigone MC, Fugazzola L, Zamproni I, Passoni A, Di Candia S, Chiumello G, et al. Persistent mild hypothyroidism associated with novel sequence variants of the DUOX2 gene in two siblings. Hum Mutat. 2005;26:395. doi: 10.1002/humu.9372. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Comments